Groove Theory #17 - Directing Robert Pattinson by Text Message

You're tuned in to Groove Theory - a newsletter about how creative ideas, careers, and live moments find their rhythm, structure, and presence in the world.

I'm your host, Howard Gray, founder of Wavetable, the experiential learning studio.

Currently: launching two new projects next week (!), unsuccessfully programming radiators

A rush-hour subway car in New York is a full slice of the city packed in a metal tube. Nurses ending night shifts, bankers checking Bloomberg, teenagers with backpacks too big for the space, someone's grandma gripping the pole, a guy deep in TikTok niches definitely about to miss his stop. Everyone’s performing the same role: minding their own damn business.

Now imagine you're a filmmaker, and you need to capture something real inside this performance. Something that feels genuinely dangerous. You have Robert Pattinson, one of the most recognizable faces in the world, and you need a train full of New Yorkers to not notice him.

You can't call "action." You can't have a visible crew. You can't control… anything.

So you stand at the other end of the car, pretending to check your phone. Your lead actor is fifteen feet away, surrounded by commuters. You can't call out directions. You can't yell cut.

So you text him what to do next.

From across the car, you watch him respond. A woman nearby shifts uncomfortably. That's real - she doesn't know she's in a movie. Neither does anyone else. When Pattinson finally exits, someone trails off behind him: "Was that Rrrr…? Was that Robert Pattinson?" By then, the scene is already captured - and no one had snapped a photo.

This is how Josh and Benny Safdie directed Robert Pattinson during the making of Good Time - a grimy, anxious thriller that went to Cannes.

The Tension

The Safdie brothers faced an impossible problem: how do you capture authentic chaos on film?

The movie industry's answer is control. Closed sets. Permits. Multiple takes. Safety. But control kills the thing they were after. The moment you say "action," everyone knows they're performing. The danger becomes pretend.

Most filmmakers accept this tradeoff. The Safdies refused it. They needed another way - one where the camera could capture something that hadn't been rehearsed, sanitized, or smoothed into movie-reality.

They found it by designing conditions that make presence unavoidable.

In Good Time, the bail bondsman was played by an actual bail bondsman. The criminal was played by Buddy Duress, fresh out of Rikers prison. Taliah Webster was cast from 600 open-call applicants not because she was the best actress, but because her real story was closest to the script.

Pattinson later described the terror and liberation of acting alongside people essentially playing themselves: "I'm always thinking another actor is judging me... But if the other person's essentially playing themselves and they think you're being inauthentic - you're genuinely being fake."

The environment created a unique kind of pressure that couldn't be manufactured any other way.

Step Into It

This isn’t just for moviemakers and actors. You know the feeling. Everyone's going through the motions. The right words, the right nods, the right faces - but something's missing. The room is performing engagement rather than actually being there. (Hello, ye olde Zoom call on a dreary Tuesday).

You have a choice: keep things smooth and hope it picks up, or introduce some friction. A question no one expects. An admission that shifts the energy. Something that makes the next moment genuinely uncertain.

Most people choose smooth. The Safdies chose friction - every time.

The Groove: Presence

Presence → Bring yourself into it. Show up fully while reading the room and creating genuine connection.

The Safdie method isn't about being chaotic. It's about designing conditions where presence isn't optional. Here are three techniques they use:

1. Asymmetric information

In Good Time, only Pattinson knew the scene structure. Everyone else had to react for real. During a confrontational scene between Connie (Pattinson) and Ray, Pattinson was the only one given the scene's structure minutes before shooting. The other actor had to respond to whatever came. When not everyone knows what's coming, reactions are real.

2. Real stakes in orchestrated moments

The Safdies refuse to close off streets. They believe it "robs the movie of its intrinsic New Yorkness and instantly makes footage look fabricated." So they shoot guerrilla-style - real locations, real people wandering through, real consequences if they get caught.

3. Tightrope by choice

They shoot on 35mm film: expensive, limited takes, no safety net of infinite digital do-overs. Skeleton crews. Rush hour subway cars. When there's genuine cost to failure, presence isn't a nice-to-have. It's survival.

The Safdie Brothers on how they use "the fabric of the city"

These techniques worked for Good Time’s $2 million budget. But what happens when the scale changes completely?

Fast forward to 2025. Josh Safdie - now directing solo for the first time since 2008 - releases Marty Supreme. It's A24's biggest budget ever: $70 million. There are 150+ speaking parts. Locations spanning New York to Japan.

The guerrilla filmmaker got a war chest. Did he abandon his methods?

Nope. The opposite. He just scaled them up.

Timothée Chalamet trained obsessively in ping pong for months. The cast is stuffed with non-actors and real personalities. And the energy Safdie first saw in Chalamet - at a party after the Good Time premiere in 2017, when the then-22-year-old was sitting against a wall, radiating "misfit" energy before anyone knew his name - that's what he built the character around.

Same methods. Bigger canvas.

1. Design the environment, not the performance.

You can't direct someone into presence (kinda oxymoronic). But you can create conditions that demand it. The Safdies don't coach actors into authenticity — they build situations where inauthenticity is impossible. The shift is from managing people to managing context.

2. Comfort is the enemy of presence.

When Safdie got a $70M budget, he didn't abandon guerrilla methods - he ramped them up. More resources usually mean more safety nets. The Safdies use them for the opposite - to create more productive discomfort, not less.

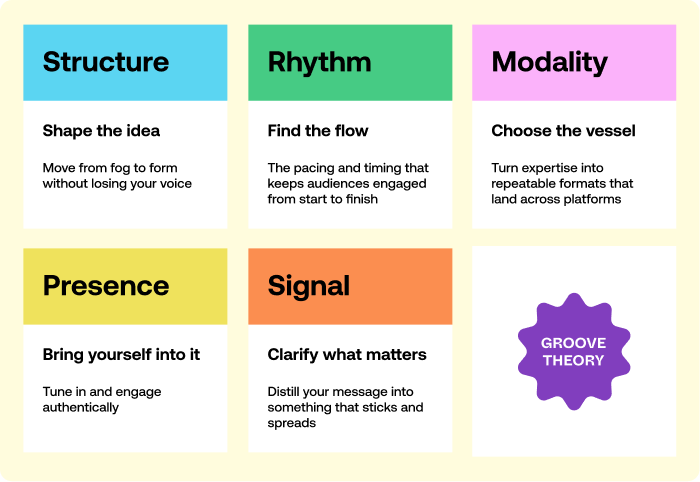

Presence is one of the five elements of Groove Theory. Learn more →

The Release

The subway scene in Good Time worked because nobody knew it was happening. The presence was real because the conditions demanded it.

The Safdie brothers’ careers are proof that you don't have to outgrow this approach - you can scale it. Bigger budgets, bigger casts, bigger stakes. But the methods remain.

The question isn't whether you can create authentic presence in high-stakes moments. It's whether you're willing to design for it.

Howard

Extended Mix

- Anxiety in the sound: The Safdies work with electronic artist Oneohtrix Point Never (Daniel Lopatin) on their scores. The Good Time soundtrack won the award at Cannes. For Uncut Gems, the brothers said the score "starts at 100 and just keeps accelerating" — maintaining tension even when the dialogue pauses. Same principle as the filmmaking: design the environment to create the feeling.

- Adam Sandler's months in the Diamond District: For Uncut Gems, Sandler shadowed jewelers at Avianne for a couple of months, learning to buy and sell diamonds, hold stones with tweezers, and open parcels without scattering gems everywhere. "There's a certain way you hold a stone," one jeweler recalled. The Safdies themselves spent a decade researching the district before filming.

- Never rehearse, always discover: The Safdies avoid traditional rehearsals - actors discover scenes in the moment. Pattinson described the Good Time experience as "survival mode," never quite knowing what would happen next. The uncertainty isn't a bug in their process - it's the point.

- Slice of life, slice of inflation: Tenuous link, but I can’t resist. I spotted this by Jay St subway station last week: 99 cents pizza no longer. I wonder about the behind the scenes conversations that led to the decision - and the paint job. (the company is still called Jay St 99cents Pizza LLC, btw)

Member discussion