Groove Theory #15 - The woman who built The French Laundry (before it was The French Laundry)

Not yet a subscriber? Sign up. Or explore the Groove Theory archive →

I'm your host Howard Gray, founder of Wavetable, the learning experience studio.

Currently: in denial of December; designing an AI-driven edutainment experience set in outer space.

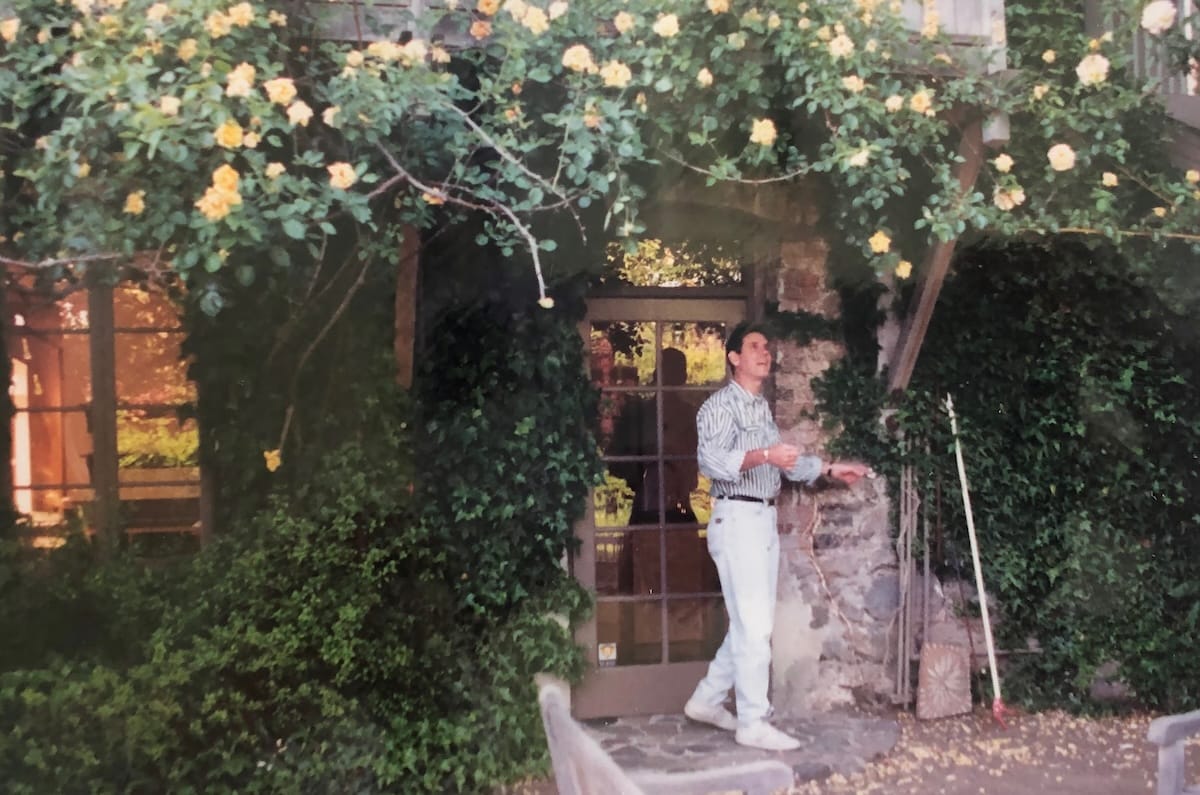

Mid 1970s in Napa Valley. A woman named Sally Schmitt is running a restaurant out of an old stone house she and her husband bought for $30,000.

The place seats 40 people. There's no menu - she cooks whatever's going. Whatever’s growing. Lettuces from the garden that morning. Vegetables still warm from the sun.

She tells diners, "This is what we have tonight."

The wine country crowd doesn't get it. They want French technique. White tablecloths. Proper courses. ‘Cos that’s high-class, dontchaknow.

Schmitt is doing something else entirely - something that doesn't have a name yet.

She's not strategising. She's not building a brand. She's just doing what makes sense to her.

It did get a name. But it'll be another decade before anyone calls it "farm-to-table."

The Tension

So much of building something new is timing. You can have the wrong idea at the right time (guilty). You can have the right idea at the wrong time (again, guilty).

Sally Schmitt spent 16 years serving food this way. Growing relationships with local farmers, foragers, and ranchers. Running a tiny restaurant that seats 40 people in a stone building in Yountville that most people drove past.

She wasn't ahead of her time. She was... on time. The culture was running late.

What actually happens when you're early is… well, nothing, really. No rejection letters, no angry critics. Just a lot of people politely not getting it. Respectful indifference. "That's nice, dear."

The restaurants that won awards in Napa during the 70s and 80s? They're gone now. Schmitt kept cooking.

Step Into It

You've probably created something that makes perfect sense to you. Clients tilt their heads. "Interesting," they say. Then 3 weeks later you find out they booked someone doing the standard thing. You fix a polite smile while boiling inside.

You could adjust. Make it more like what they're used to. You'd get more bookings. Better testimonials. Maybe scale up a team.

Or you keep doing the version that feels right to you. Even when it means years of "not quite" responses. Even when your friends ask why you're making it so hard on yourself.

The actual question isn't "Should I compromise?". It's harder than that. It’s "How do I know I'm not just... wrong?"

When nobody gets what you're building, what's the difference between visionary and delusional? The line isn’t just thin… it’s often invisible.

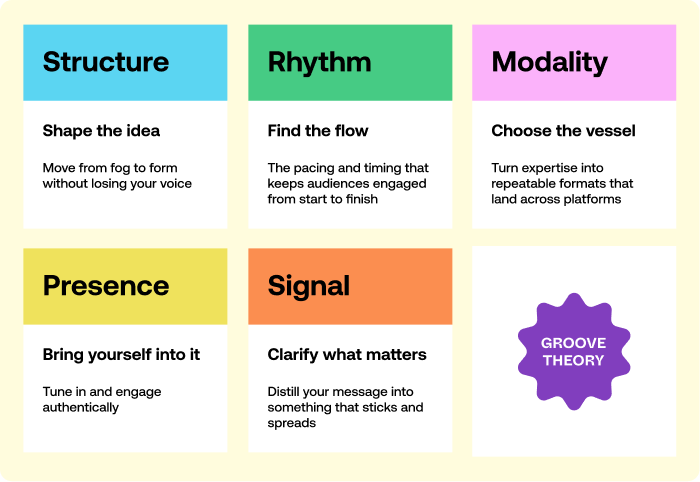

The Groove: Signal

Signal → Clarify what matters. Distill your message into something that sticks and spreads.

Let’s fast forward two decades. In 1994, Schmitt gets an offer she decides to take. The buyer had been searching for a place to create something new. He kept her name for it: The French Laundry.

The buyer? Thomas Keller.

Keller kept Schmitt's philosophy - the garden, the relationships with farmers, the focus on what's in season. He kept cooking in Sally's kitchen for a year before renovating. Her green stove with its blue hood. Her minimalist design that felt like home. Years later, he'd say they were 'always following Don and Sally Schmitt's roadmap.'

The French Laundry became legendary. Three Michelin stars. The best restaurant in America. The place every serious chef wanted to work.

How? Keller had the training. The French technique, the Michelin precision. But by '94, he also had the right moment. He didn't have to convince anyone that local ingredients mattered. Alice Waters had made that case at Chez Panisse. The culture had caught up. Keller got to build on a foundation that people finally understood.

Sally Schmitt had been sending that signal for 16 years. She just did it before anyone was listening.

1) Doing it early looks exactly like doing it wrong

In 1978, Schmitt's approach looked small. Uncommercial. A bit quaint. Now it's how we define a good restaurant. The work that lasts often starts as the work that doesn't make sense yet. There's no way around that.

2) You can't talk people into getting it before they're ready

Schmitt didn't spend years explaining farm-to-table. She just kept cooking. The work was the argument. By the time Keller showed up, she'd built 16 years of proof. When the culture finally catches up, they're not listening to your pitch deck - they're looking at what you actually did.

Signal is one of the five elements of Groove Theory. Learn more →

The Release

Most profiles of The French Laundry start with Keller. The visionary. The perfectionist. Three Michelin stars.

Ask who came before him, you mostly get blank stares.

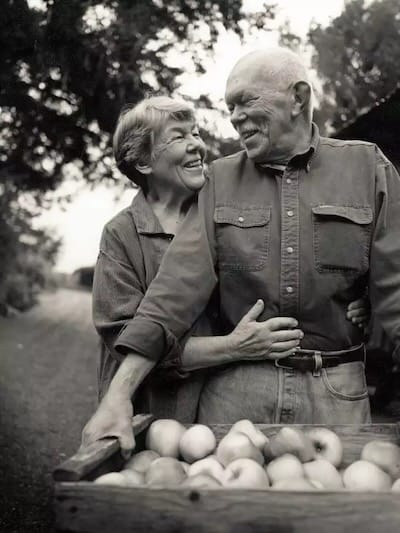

Sally Schmitt died in 2022, aged 90. Some obituaries mentioned her restaurant. Few connected her to what The French Laundry became.

But the people who know, know. Keller does. The old Napa families do. The farmers she worked with remember.

She built the foundation. He built the cathedral.

That's not a sad story. That's just how signals work when they're ahead of their time.

This can be hard to swallow. Feels disempowering even. We're all worried about getting credit. Getting seen. Getting our name attached to the thing we built. And look - maybe we should be.

Maybe Schmitt deserved more recognition while she was alive. Maybe it's not fair that Keller's name is on everything and hers barely registers.

But fair doesn't change the pattern. Signals travel. Foundations get built on. The work that's too early often becomes someone else's breakthrough.

You can fight that, or you can decide it's not the point.

Schmitt kept cooking. Before The French Laundry, during it, after she sold it. She just kept cooking.

Howard

Extended Mix

- The Best Chef in the World: Oscar winner Ben Proudfoot's Breakwater Studios made a documentary on Sally Schmitt in 2022. (Fun fact: Josh Upton, featured in Groove Theory #5, works closely with the Breakwater team)

- The French Laundry building: Built in 1900 as a steam laundry, the stone structure sat empty for years before Schmitt and her husband bought it in 1978. They chose the name because… well, that's what it used to be.

- Sally's choice: She raised five children while running the restaurant. She didn't chase awards or fame. "The goal in life really is about people and family," she said. She led what Proudfoot calls "a very high-quality life" - one that didn't include recognition or money, but meant something else entirely.

No spam, no sharing to third party. Only you and me.

Member discussion